The Long-Standing Rosen-Durling Test used to Assess Nonobviousness of Design Patents is OVERRULED

The long-standing Rosen-Durling test used to assess nonobviousness of design patents required a primary reference must be “basically the same” as the challenged design claim, and further that any secondary references must be “so related”. The Federal Circuit had never considered the merits of the Rosen-Durling test.

Hearing LKQ Corp. v. GM Glob. Tech. Operations LLC, the Federal Circuit ruled en banc that the Rosen-Durling approach was too inconsistent with Congress’s statutory scheme for design patents, which intends for the same conditions for patentability that apply to utility patents apply to also apply design patents. This decision was precedential and represents a major shift in design patent law.

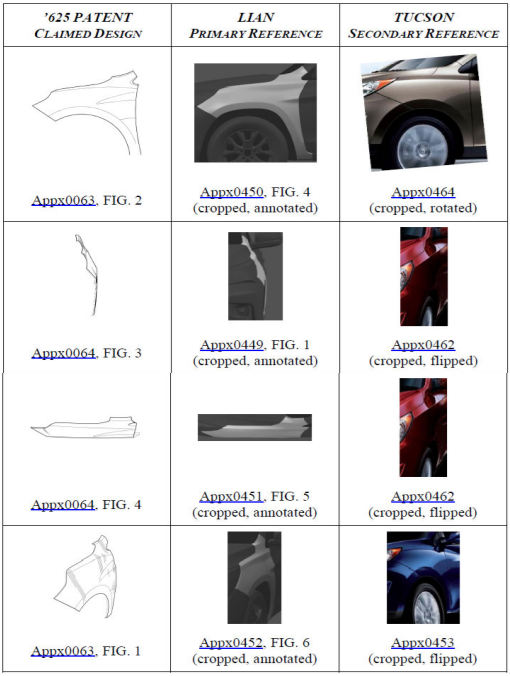

GM Global Technology LLC (“GM”) owns U.S. Design Patent No. D797,625, which claims a design for a vehicle’s front fender. This design is used in GM’s 2018–2020 Chevrolet Equinox. LKQ had presented the following comparisons between the D’625 patent, Lian, and Tucson:

The Federal Circuit aims to reset the obviousness standard to the one set forth Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City, which involved utility patents. 383 U.S. 1 (1966). The Court in Graham explained that the ultimate question of obviousness is one of law based on “several basic factual inquiries.” Id. at 17. The Court elaborated that under § 103, these factual inquiries include “the scope and content of the prior art”; “differences between the prior art and the claims at issue”; and “the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art.” Id. In KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007), the United States Supreme Court explained that Graham “set forth an expansive and flexible approach” in determining obviousness.

The Supreme Court further confirmed that such a flexible approach is appropriate where design patents are concerned. See Smith v. Whitman Saddle Co., 148 U.S. 674 (1893). Although, at that time, patent law did not speak of obviousness. The Whitman Saddle Court addressed the matter by reference to “the inventive faculty.” 148 U.S. at 679. The reasoning of Whitman Saddle carries over to the modern § 103 standard of obviousness.

The Rosen-Durling test requirements—that (1) the primary reference be “basically the same” as the challenged design claim; and (2) any secondary references be “so related” to the primary reference that features in one would suggest application of those features to the other—are therefore improperly rigid in view of the precedents set forth in KSR and Whitman Saddle.

Now that Rosen and Durling are overruled, the framework for evaluating obviousness of design patent is guided by the language of § 103, as well as the Supreme Court’s and the Federal Circuit’s precedent (see, e.g., Hupp v. Siroflex of Am., Inc., 122 F.3d 1456 (Fed. Cir. 1997)) on obviousness in both the design and utility patent contexts. Invalidity based on obviousness of a patented design is determined based on factual criteria similar to those that have been developed as analytical tools for reviewing the validity of a utility patent under § 103, that is, on application of the Graham factors.

Because this approach casts aside a threshold “so-related” requirement that is used in the Rosen-Durling test, the Federal Circuit explicitly held there is still a threshold analogous art requirement. Specifically, a flexible fact-based analysis of whether the references are analogous art applies for design patents in a manner similar to utility patents.

Analogous art for a design patent includes art from the same field of endeavor as the article of manufacture of the claimed design. See 35 U.S.C. § 171(a) (“Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor . . . .” (emphasis added)). The scope of the prior art is not the universe of abstract design and artistic creativity, but designs of the same article of manufacture or of articles sufficiently similar that a person of ordinary skill would look to such articles for their designs.

The Federal Circuit chose not to delineate the full and precise contours of the analogous art test for design patents, but stated the second way in which a reference can qualify as analogous art with respect to utility patents (“if the reference is not within the field of the inventor’s endeavor, whether the reference still is reasonably pertinent”), does not seem to apply for design patents. Whether a prior art design is analogous to the claimed design for an article of manufacture is a fact question to be addressed on a case-by-case basis and will be left to future cases to further develop the application of this standard.

Once references are determined to be analogous art, the Federal Circuit confirmed there must be some record-supported reason (without hindsight) that an ordinary designer in the field of the article of manufacture would have modified the primary reference with the feature(s) from the secondary reference(s) to create the same overall appearance as the claimed design. Campbell Soup, Co. v. Gamon Plus, Inc., 10 F.4th 1268 (Fed. Cir. 2021) (discussing the question of whether “an ordinary designer would have modified the primary reference to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design”).

Consistent with Graham, the obviousness inquiry for design patents still requires assessment of secondary considerations as indicia of obviousness or nonobviousness, when evidence of such considerations is presented. Such secondary considerations include commercial success, long felt but unsolved needs, and failure of others, can be utilized to give light to the circumstances surrounding the origin of the subject matter sought to be patented. In prior cases involving design patents, commercial success, industry praise, and copying may demonstrate nonobviousness of design patents. See e.g., MRC Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter Mfg., LLP, 747 F.3d 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

Gregory Lars Gunnerson is a Partner, Intellectual Property Attorney in the Mechanical and Electrical Patent Practice Groups, and Chair of the Design Patent Practice Group at McKee, Voorhees & Sease, PLC. For additional information please visit www.ipmvs.com or contact Lars directly via email at gregory.gunnerson@ipmvs.com.

← Return to Filewrapper